"Your life is about to change!"

an excerpt from a memoir in progress

Cid Corman’s two major volumes of poetry, Sun Rock Man and Livingdying, kept me company during the summer of 1999. The books were listed in a New Directions Publishing catalogue for a few dollars each (within my budget) and his name was familiar to me, but I didn’t know his poetry. I was curious. And the titles enchanted me — they were short poems unto themselves.

I spent long air-conditioned afternoons cocooned within their pages. The only disruption was the old air conditioner my landlord loaned me. Every few hours, it leaked all over the windowsill, requiring me to mop up the puddle with an already saturated beach towel.

Sun Rock Man is one of the Cid’s earliest books, written in a small, poor Italian village. The poems burst with sunlight and local detail captured by the curious eye of a traveler. The work reminded me of William Carlos Williams, the poet Allen Ginsberg implored me to read a few years earlier. I knew Williams’ work well by then and clearly saw the influence — the brevity and crisp imagery — but Corman’s poems felt more packed-in with rich tapestries of speech-driven sound, a subtle music that easily leaves and lingers on the tongue.

The Tufa

I hear rain rot

rock. Raking death in.

Or is it life

divvying whatlittle there is

out? The whitewash

relieved by tufts

of saxifragenestling in pocks

of the walls of

a man’s house. A

window yawns andlooks out of it-

self at a row

of far cypress

and a blank sky.

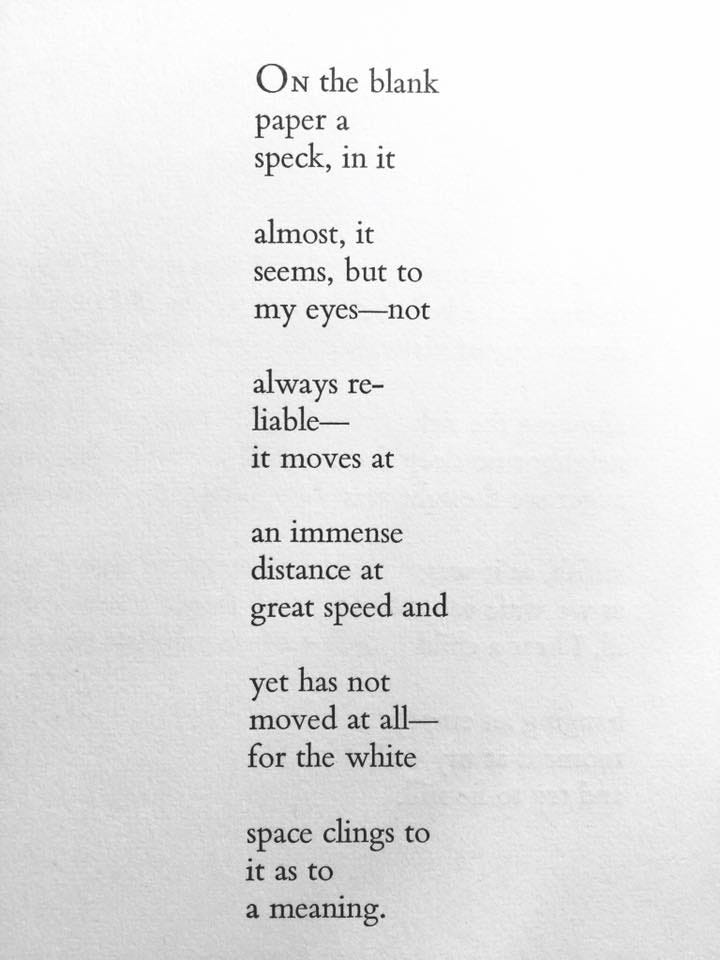

Livingdying was no different in that sense, the subtle music of the language and the chiseled images, but the poems were shorter, skinnier, razor-sharp meditations on mortality and the act of making meaning, and the human beauty in the uselessness of such a feat. Nevertheless, we continue to speak, sing, and write poetry. As Cid put it in a poem, “We remain human.”

Between Kenneth Rexroth’s 100 Poems from the Japanese, the poetry of Lorine Niedecker, and the Corman books, I found a source of wonder and creative momentum that drove me deeper into my notebooks. I wanted to nail a poem like that, succinct, but each syllable imbued with the weight of the world, like they did.

I found Cid’s address in a book of Lorine Niedecker’s poetry. He was her literary executor. The book was published decades ago, so I wasn’t sure if the Kyoto, Japan address was still his, but I wrote him a letter and sent a few of my poems anyway.

Two weeks later, I opened the mailbox beside the door of my studio apartment. The sky-blue aerogramme from Japan shined inside of the mailbox as if it were made of neon and I immediately noticed the handwritten name “Corman.” As I pulled it out of the box, I read the poem typed on the front of the envelope:

Poetry is that

conversation we could not

otherwise have had.

With one hand I held the aerogramme open, and with the other I gripped the hot metal handrail to keep myself from falling. I was dizzy with joy.

The typed letter began: “Your life is about to change!” I let that opening sentence roll around in my mind for a few minutes as I stood there swaying in the sun.

The memory is infused with the scent of cut grass and the intense heat — a ritual of purification before beginning my apprenticeship as a poet.

Your life is about to change…

And he was right.

I felt this. Wonderful!

I cannot wait to read more! Soaked every bit of it in.